Japanese Beetle (Popillia japonica)

Japanese Beetles (Popillia japonica) are especially prolific this summer, voraciously consuming the leaves, flowers and buds of herbaceous (non-woody) plants, shrubs and trees. They were first discovered at a nursery in New Jersey in 1916, probably introduced here with imported nursery stock. Now widespread east of the Mississippi River in the United States and southern Canada, these insects are destructive pests in North America because the natural predators with which they evolved are not present here to keep them in check.

Red Chokeberry (Photinia Pyrifolia) leaves skeletonized by Japanese Beetles

What can you do to combat these critters? Enlist the help of some predatory insects that are native to North America.

Scolia dubia on Boneset (Eupatorium species). Scolia dubia is known to prey on the larvae of Japanese Beetles.

Scoliid wasps prey on the larvae of scarab beetles to feed their own larvae. Japanese Beetles are a species of scarab beetle. Female Japanese Beetles burrow a few inches into the ground to lay their eggs. Their larvae, often called grubs, develop underground and feed on the roots of plants. Female scoliid wasps find and enter the underground burrows of Japanese and other scarab beetles, and lay an egg on each grub. The wasp larva hatches and consumes the grub. Two species of scoliid wasps are shown in this post, Scolia dubia and Scolia bicincta.

Scolia dubia on Grass-leaved Goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

How can you entice these beneficial wasps to patrol your property? They can be bought with food. The adult wasps drink nectar from flowers, usually flowers that have short tubes, arranged in dense clusters that provide a landing platform for the wasp. Mountain mints and many aster family members fit this description. They seem especially partial to goldenrods and bonesets, in addition to the mountain mints.

Scolia bicincta on Hoary Mountain Mint (Pycnanthemum incanum). Scolia bicincta may also be a Japanese Beetle predator.

These beneficial wasps are hairy, helping to make them to be effective pollinators of the plants they visit for nectar. The pollen is likely to adhere to their hairy bodies and be carried to another plant for deposit.

Scolia bicincta on Hoary Mountain Mint (Pycnanthemum incanum).

You may be worried about having wasps around, because of their reputation for stinging. While that reputation may be deserved for some social wasp species, like the Yellowjackets, it’s more a case of guilt by hasty generalization for solitary wasps like the scoliids. Social wasps live in colonies, which they aggressively defend from intruders. But scoliids, like many wasp species, are solitary. So there is no colony to defend. Stingers are really ovipositors (egg laying structures) that can be used for two purposes. Females may use the ovipositor to sting and subdue their prey, and also to lay their eggs. Male wasps and bees don’t lay eggs, so the don’t have ovipositors, and can’t sting. Solitary wasps like the scoliids are quite gentle, and would generally have no reason to sting a person.

Eastern Yellowjacket (Vespula maculifrons) on Goldenrod (Solidago species)

The Wheel Bug (Arilus cristatus) is a type of assassin bug that is happy to devour adult Japanese Beetles. Wheel Bugs hunt their prey by blending in with a plant. They wait for a hapless victim to come close enough to grab it with their somewhat hairy and sticky front legs, then stab it with their beak, injecting enzymes that paralyze and then liquefy their victim’s innards. The Wheel Bug then slurps up the resulting insect smoothie, with the victim’s exoskeleton acting as a to-go cup.

Wheel Bug (Arilus cristatus) preying on Japanese Beetle; more Japanese Beetles continue to eat in upper left.

Japanese Beetle grubs (larvae) are especially fond of eating the roots of lawn grasses. As a result, lawns are the favored location for Japanese Beetles to excavate a burrow for their eggs. Replacing as much lawn as possible with a mix of herbaceous plants, shrubs and trees will minimize the habitat available to Japanese Beetles for reproduction. Reduced habitat means fewer Japanese Beetles.

Japanese Beetles (Popillia japonica)

What can you do to combat Japanese Beetles? In order to attract beneficial insects like those shown here, be sure you have a variety of plants native to your area. Take away the Japanese Beetle’s preferred habitat by minimizing the size of your lawn. There will be a corresponding reduction in the number of Japanese Beetles you see.

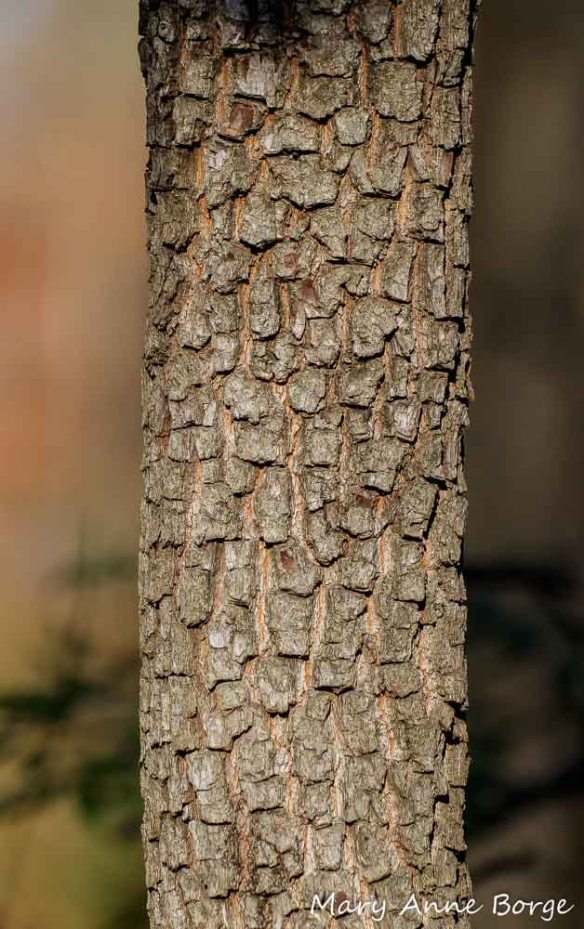

Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) leaf skeletonized by Japanese Beetles

Related posts

Mountain Mints are Pollinator Magnets!

Asters Yield a Treasure Trove

Fall Allergies? Don’t Blame Goldenrod!

Resources

Eaton, Eric R.; Kauffman, Ken. Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America. 2007.

USDA Japanese Beetles

Beneficial Insects in the Garden